Uncategorized

Did Michael Mundashi knowingly and intentionally commit the offence of obtaining $127,346.10 from TAP ZAMBIA LTD under false pretence?

Published

2 years agoon

By

Peter SmithIn order to determine whether Michael Mundashi committed a crime of obtaining $127,346.10 under false pretence, it is important that the allegations are supported by common cause facts.

Mr. Mundashi is a senior practicing professional lawyer in Zambia.

As bavkground, it is true and fact that Mr. Mundashi using the agency of MMLP was paid an amount of $127,346.10 pursuant to a letter of invoice issued to DMH Attorneys, a law firm incorporated in terms of the laws of Zimbabwe, in relation to scope of work detailed on the invoice in relation to a claim by SMM Holdings Private Limited (SMM), a private company whose Zimbabwean control and management was divested from its UK registered parent, SMM Holdings Limited (SMMH) and placed extrajudicially under the control of Mr. Afaras Gwaradzimba, a Zimbabwean practicing Chartered Accountant.

It is not in dispute they Gwaradzimba was appointed by the then Ministrt of Justice, Mr Patrick Chinamasa, to act as Administrator of SMM under reconstruction in terms of a decree promulgated by the late President Mugabe.

The said decree was issued on 7 September 2004.

Purporting to act on this decree, Mr Gwaradzimba instructed Mr Edwin Manikai, Managing Partner of DMH, a law firm registered as such to act for SMM under reconstruction to engage MMLP to prosecute a claim in the High Court of Zimbabwe.

It is not in dispute that SMM under reconstruction was an organ of the government of Zimbabwe for the following reasons that must have been known by Mr. Mundashi when he was approaches to act on behalf of this entity:

- SMM was prior to the issusnce of the decree a private company operating in terms of the Companies Act of Zimbabwe

- The effect of the reconstruction order was to divest the shareholder of the company of the right and freedom of appointing and dismissing directors of the company as provided in terms of the companies act, a law of general application.

- The shareholder of SMM was not informed of the change of control of the company.

- The Minister of Justice purported that the state was a creditor of the company and as such was indebted to the state and the company was determined to be insolvent.

- According the government without any fur process of the law and without the involvement of the judiciary and using state of emergency powers permitted the Minister to issue a reconstruction order in relation to SMM whose effect was to alienate the shareholder from its subsidiary company and for the Minister to use the force of law to dismiss the board and replace it with his appointee.

- The Administrator so appointed occupied an administrative position in relation to SMM but owed a duty to the Minister of Justice as the Appointing Authority.

- In terms of the decree and associated regulations, Mr Gwaradzimba owed no duty to the company but to the Minister unlike a judicial manager or liquidator who is appointed by the court.

- It is law in Zimbabwe and Zambia, that a representative of a company who is appointed pursuant to judicial proceedings owes a fiduciary duty to the insolvent estate and as such must be independent and impartial.

- Thd distinguishing feature of this Administrator is thst he was appointed by a purported representative of a creditor and as such was not independent.

- The laws of Zimbabwe have no extraterritorial application and as such the authority to represent SMM was limited solely in the jurisdiction of Zimbabwe and not Zambia as this violated Zimbabwean and Zambian laws.

- The authority to act for SMM under reconstruction did not come from the company pursuant to any resolution but was derived from the appointment of Gwaradximba to assume the control of SMM under reconstruction in Zimbabwe.

The first legal question that needs to be investigated is the legal status of a company under reconstruction in terms of a decree that has no precedent or equivalent in Zambia.

Mr Mundashi knew that the shareholder listed on PACRA records showed that two companies were the registered shareholders as follows: Africa Resources Limited (ARL) and Africa Construction Limite (ACL).

Both companies were registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). ACL was wholly owned by ARL, a company that was a shareholder of SMM’s parent, SMMH.

ARL’s sole shareholder was Mr. Mutumwa Mawere, a Zimbabwean-born South African citizen and resident.

It was known to Mr. Mundashi that there was no legal ownership nexus between SMM under reconstruction and TAP.

In terms of Zambian law as is the case universally, the right to appoint directors is vested in shareholders.

Accordingly, Mr Mundashi knew that no Zambian court had title and jurisdiction to grant any order whose effect was to deprive or divest shareholders of the right to appoint or dismiss directors let alone to suspend their enjoyment of their constitutional rights in relation to their company.

Mr Mundashi’s scope of activities was to search the records of TAP to determine the company’s legal structure and ownership.

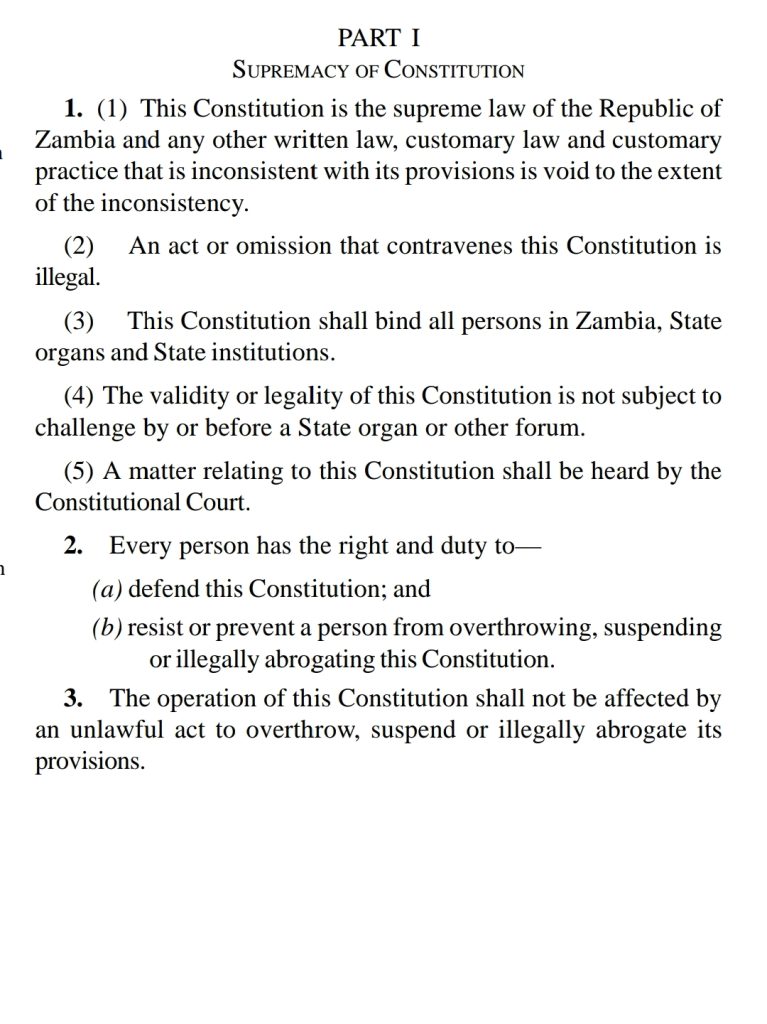

Notwithstanding, Mr Mundashi knowingly and wilfully with intent to prejudice the shareholders of TAP of their constitutional right to property and freedoms in relation to their company, participated in conduct that is inconsistent with the prescripts of the Zambian constitution that any law, practice and conduct that is inconsistent with the supremacy of the Zambian constitution is invalid to the extent of its inconsistency.

Mr Mundashi knew that as a citizen of Zambia he like all persons had a right and duty to defend the Zambian constitution as the supreme law to permit himself to be party to conduct whose effect was to make a Zimbabwean decree a law of Zambia and superior to the constitution.

Mr Mundashi in terms of the Zanbian law is required to take an oath to promote, protect and uphold the constitution of the country as the supreme law and as such his oath prohibited him from accepting a mandate derived from a law and conduct that is inconsistent with the constitution of Zambia.

With his knowledge and complicity, the Zanbian jurisdictional space was invaded directly using the weapon of a decree.

He had knowledge that this decree offended the rule of Zambia and as such it was invalid.

He proceeded to accept SMM under reconstruction as his firm’s client fully alive to the illegality and unconstitutionality of the scheme and was paid a deposit of $10,000 to commence the hatchet job.

The question that arises is whether a right acquired that is invalid and of force and effect in Zambia was a right at all.

The law is clear on this and the constitution is instructive that nothing turns on an illegality.

The conduct to institute proceedings in Zambia based on an illegality in terms of the Zambian constitution as follows:

Mr Mundashi openly and audaciously fully associated himself with cobduct that was inconsistent with the above.

By acceoting the poison chalice, he chose to uphold the Zimbabwean law in preference of his duty to protect the Zambian constitution that he took an oath to uphold and protect.

He knew that the sole purpose of his mandate was to defeat the ends of justice by asserting a falsehood that by virtue of this decree, a Zambian court had jurisdiction to recognize and enforce it with known prejudice to the constitution and the directly affected parties being the bona fide shareholders and their apponted directors who were dismissed pursuant to an order tainted by misrepresentations and fraud.

The fraud on the court is unmistakable. An order was purportedly granted to a fraudster disguised as a company.

Mr Mundashi knew that the effect of the reconstruction order was to remove SMM from the ambit or jurisdiction of the Companies Act, a law of geveral application, and place its affairs in terms of the Reconstruction Act, a law that is not recognizable in Zambia and that only applies in totalitarian regimes.

In the premises, Mundashi knew that his purported client was not a company but a creature of statute and as such was an organ of a foreign state.

He also knew that the Administrator lackef any jurisdiction to represent neither a company nor an organ of a foreign state.

In the premises, Mundashi’s client was not a company as he purported by the government of Zimbabwe that hijacked the control and management of SMM and placed it under its exclusive control using the force of public power.

Mundashi knew that the scheme to inavde and capture TAP could not be prosecuted without the knowledge and approval of the government of Zimbabwe’s alter ego.

Ths purported right that Mundashi assertef in relation to Zambian proceedings were that of the government of Zimbabwe.

To this end, a foreign government and a member of SADC knowingly appointed Mundashi using the agency of Manikai and Gwaradzimba to undermine the rule of law in Zambia.

It is worth highlighting that the corrupt Kajimanga J judgment was overturned in June 2008 by the Supreme Court of Zambia.

MMLP on 5 February 2006 invoiced DMH for successfully weaponozing the Kajimanga J judgment.

Gwaradzimba when askec by a director to explain why he participated in the fraud, this is what he had to say:

Listen to Gwaradzimba Exposed by TAP Zambia by Mutumwa Mawere on #SoundCloud

https://on.soundcloud.com/A8BS6

Mr Gearadzimba said that he was under the impression that TAP was owned by SMM under reconstruction.

He sssrted that when the reconstruction order it applied to all Zimbabwean and non- Zimbabwean companies like TAP.

He boldly asserted that he was entitled to receive administration fees in terms of the Zimbabwean law.

He claimed that he was not a party to the proceedings and he approached the court to test an allegation that SMM under reconstruction had an owbership nexus with TAP.

He denied that the Mundashi prosecuted matter was fraudulent yet the matter was handled on the basis of a misrepresentation to court that TAP was an associate of SMM under reconstruction when this was not the case.

Does the fact that MMLP invoiced DMH, a Zimbabwean law firm with no address in Zambia, on the 7 February 2006 following the judgment of Kajimanga J or before the parties including TAP could even decide to appeal expose a broken Zambian system at the time.

Mr Mundashi as a lawyer would have known the rules of court that give litigants an opportunity to challenge a judgment yet in this case he already knew that after divesting Mawere of all his assets the strategic Kajimannga J judgment left him with no funds to challenge the judgment clearly tainted by fraud.

It is also ironic that on the same day the judgment was granted by court, Gwaradzinba without waiting for the affected parties to make an election to challenge the judgment, proceeded to enforce the judgment by fusnissing the TAP board.

The letter addressed to the TAP directors was copied to Mundashi who knew that illegality inherent in using a foreign law that is inconsistent with the Zambian constitution to to usurp the right and freedoms of shareholders in relation the appointment of directors.

The invoice was only made after the removal of directors by Gwaradzimba using the Kajimanga J judgment as authority and in the knowledge that Manikai had been appointed unlawfully as director of TAP.

The sequence of events expose a choreographed scheme invclving Manikai as a director of TAP receiving the invoice snd passing it to Gwaradzimba who then instructed TAP management to pay to MMLP.

The invoice that was addressed to DMH was with the authority of Gwaradximba whose relationship with TAP was fraudulently established using the court in which MMLP was the agent to hijack the company’s control so as to benefit from the proceeds of a criminal project.

MMLP got its share from the project from TAP, the victim of crime.

TAP was instructed to treat the unlawful payment to MMLP as an intercompany transaction when in truth and fact TAP had no such relationship with SMM under reconstruction.

Mundashi’s did not provide any services to TAP to justify the payment against no known paperwork.

It would be interesting to investigate what the books of MMLP showed to reflect the payment and receipt of the funds.

Clearly, without an agreement between DMH and TAP providing for TAP paying on behalf of DMH, the transaction would fall within the ambit of money laundering activity.

Mindashi knew that there were no services rendered to TAP and TAP equally knew that the payment was authorized by Gwaradzimba whose relationship with the company was solely based on a judgment that the purported services related to.

This confirns a conspiracy between Mundashi, Manikai, Gwaradzimba and possibly Kajumanga J that the outcome of the court proceedings was predetermined and MMLP was to work on success basis and as such DMH’s relationship with MMLP was part of a corrupt enterprise.

It is true and fact that DMH and SMM had no funds to pay MMLP for the services provided and that the instruction to TAP to pay on behalf of DMH was a sham transaction as all parties knew in advance how the stolen funds would be distributed using the court order as a weapon.

To date neither SMM under reconstruction nor DMH have paid TAP any funds in liue of this theft.

It is not in dispute that MMLP obtained the $127,346.10 under False Pretenses with the intent to defraud TAP.

To the extent that these funds exchanged hands between TAP and MMLP as a consequence of the Kajimanga J judgement, actual fraud did take place.

Absent the false pretenses, TAP would not have been prejudiced.

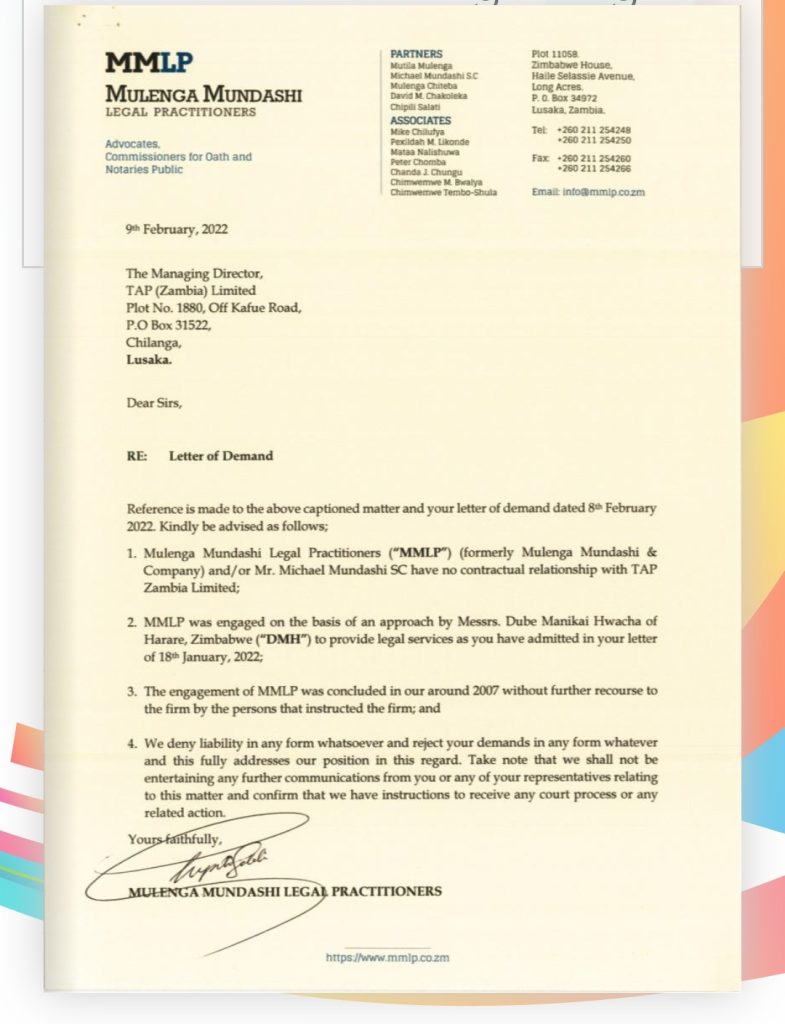

It is significant that on 9 February 2022, Mundashi confirmed that his firn had no contractual relationship with TAP that would justify the payment.

In the prenises and to the extent that TAP had no legal basis to make any payment to MMLP on behalf of an unrelated party, DMH, a Zimbabwean law firm with no legal nexus with TAP, apart from the fact that TAP was the victim of an criminal enterprise in which MMLP was a driving force in its prosecution in Zambia using a foreign law.

To the extent that MMLP rendered services in the prosecution of an illegal and constitutionally invalid enterprise, the question that should follow is whether this determination by MMLP that it was entitled to proceeds of crime should stand.

Warning: Undefined variable $user_ID in /home/iniafrica/public_html/wp-content/themes/zox-news/comments.php on line 49

You must be logged in to post a comment Login